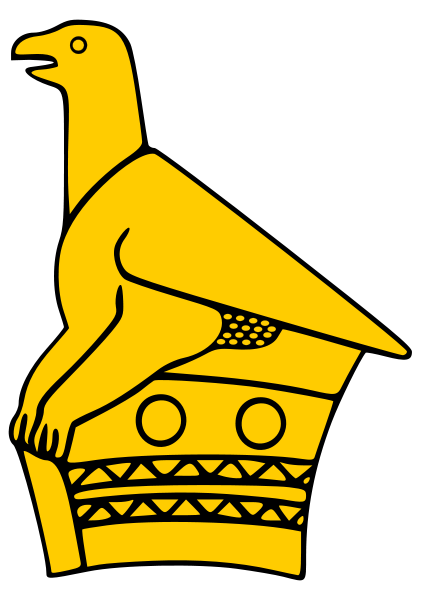

The Kia

Pioneer Days

Why did the Matabele wait so long before reacting?

Lobengula had disappeared at the end of 1893 and rumours as to his fate were varied and numerous; as far as we know, he never reappeared. The Matabele State in 1896 existed much as it had before the invasion except that as in 1869, they were without a king. For the most part, the indunas remained in control of their territories and were unanimous in their desire to raise a new king but all were divided by factionalism and differences of opinion as to the best way to deal with the invaders. Cobbing (1976) has argued that they also needed to plan their military strategy in great deal because anything less than a full-scale war would have been put down by the white forces extant in the country. Time was needed for mobilisation, stashing of foods, stockpiling of weapons and ammunitions and so on. Most important however, was the desire to raise a new king, but custom dictated that a period of not less than a year and, ideally two, should pass before making any such moves. Several meetings took place in 1894-95 most organised by senior members of the royal family notably Lobengula's oldest remaining son in the country – Nyamanda.

Who was Nyamanda?

He remains the unrecognised third King of the Matabele Nation. There are conflicting accounts of the year of his birth as well as his relationship with Lobengula. Burrett (1996: 40) claims Nyamanda was born in 1873 (which would make him completely eligible for the throne) and was a favored son of Lobengula and was designated as heir-apparent. In contrast Clarke (2010) and Cobbing (1976) acknowledge the respect with which Nyamanda was treated by the other indunas but do not accept he was favored in any way by Lobengula nor had he any right to the throne. Nevertheless his influence was such that Burrett (1996) claims Nyamanda was elected king on June 25, 1896 by a council of indunas in the Matobo Hills. Together with Umlugulu, Nyamanda played an important role in coordinating the risings as well as serving as an important figurehead, bringing into the fray many groups who might have otherwise remained neutral.

Describe the disposition of Matabele forces in March 1896.

This section relies heavily on Cobbing's (1976) thesis. Matabele leadership had merged into three main groups, each of which was related to the other by kinship, culture and objectives but were widely separated by distance and communication difficulties. To the north were Queen Lozikeyi and Nyamanda allied with several regiments who influence stretched as far as Gweru. Within their sphere of influence were the collaborators, Gambo Sithole and Mtshani Khumalo (more on them and the idea of working for the whites in a later briefing). A second grouping, with no central leadership, was based in the Matobo Hills and included the formidable leaders Umlugulu, Mnthwani Dhlodhlo (Lozikeyi's brother) and Babyaan. The last grouping embraced the people of Amakandeni and Godhlwayo to the east and south-east of the Mulugwane Hills, stretching into the Fort Rixon area and Insiza district; an influential leader here was Somashulana Dhlodhlo.

What can we regard as the catalyst?

As we covered in a briefing earlier this year, Jameson's raid can be considered as the moment of opportunity the Matabele had been waiting for. Jameson had taken all of the white police with him in his disastrous attempt to conquer the Transvaal, leaving many areas with an even smaller white presence than they had had previously. The murder of the native policemen in March seems to have been a premature start since Clarke (2010) and Cobbing (1976, 1977) have clearly shown that the traditional leaders had wanted to finish harvesting their crops. We have it on good authority from Selous that the failure of Jameson's Raid seemed to be a pivotal moment. "Umlugulu… often came to see me and always questioned me very closely as to what had actually happened in the Transvaal… I could see he was very anxious to get at the truth". As Blake (1977) succinctly states, the "whites were vulnerable as never before".

And what about superstitions?

Before and during 1896 a series of natural events which, by their frequency and effect, seemed a supernatural sign. The year was one of drought, and on top of this there had been plagues of locusts, rinderpest had struck, and in February 1896, there had been a full eclipse of the moon. All these events seem to have added to the impetus to rebellion that had already been set in motion by the Matabele aristocracy. The BSACo report squarely blamed the superstitious nature of their peoples as a prime cause of the uprising but later authors have preferred to focus on political and economic influences.

Sourced from the Zanj Financial Network 'Zfn', Harare, Zimbabwe, email briefing dated 14 March 2011

South Devon Sound Radio

South Devon Sound Radio Museum of hp Calculators

Museum of hp Calculators Apollo Flight Journal

Apollo Flight Journal Apollo Lunar Surface Journal

Apollo Lunar Surface Journal Cloudy Nights Classic Telescopes

Cloudy Nights Classic Telescopes martini in the morning - The Lounge Sound

martini in the morning - The Lounge Sound The Savanna - Saffer Shops in London

The Savanna - Saffer Shops in London Linux Mint

Linux Mint

Movement for Democratic Change

Movement for Democratic Change