Pioneer Days

Hang on… the Matabele left an escape route?

Echoing Rhodesian opinion of the time, Rhodes' friend and confidant Hans Sauer wrote in 1937, "The Mangwe Pass winds its way through the Matopos for a distance of between twenty and thirty miles… Fortunately for us, the Matabele headquarters were entirely ignorant of the art of war. This failure led them to leave the Mangwe Pass, the only road to the south, unoccupied and practically unmolested so that the Matabeleland half of Southern Rhodesia could feed and provision itself. If the Matabele had effectively occupied the Pass, the surviving European population… would have soon found itself in straits". Even today there is a general misapprehension that the Matabele were determined to leave this road open to give the whites in Bulawayo an easy retreat, thus tempting them to abandon the country. This idea is based on a rumor of the times. Several authors, including Ransford, Ranger and Blake have shown that the truth, as usual, is more elusive. Blake (1977), following Ranger's (1967) book relates how the opposition of the Kalanga in the area influenced the shrine at Mangwe to repudiate any involvement in the uprising (which makes a mockery of Burnham's claims to have killed Mwali; see the next briefing). In addition, Matabele leaders in the area, including Gampu, Faku, Maphisa and Nyameni were working with the whites and offered the necessary protection in the south against attack (see the next briefing).

So that's how they got to build the forts

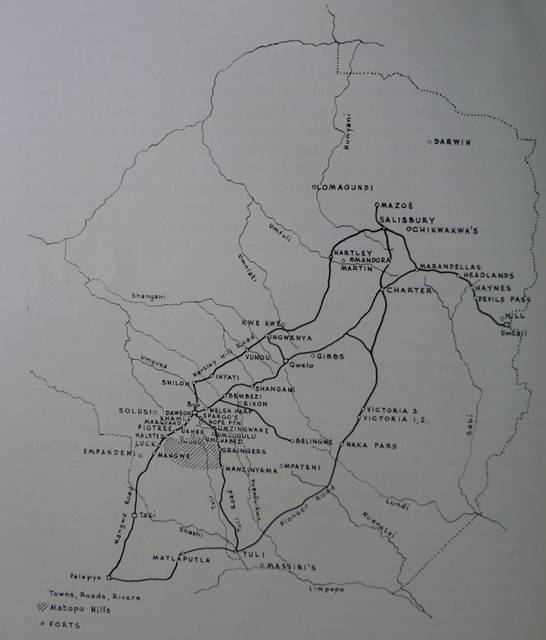

Map, modified from Garlake (1965) showing the position of the major forts in Rhodesia, 1896-1897

Selous was tasked with building a series of forts linking Bulawayo and Mangwe, thus maintaining a link with Bechuanaland and the south. Using the ring of collaborating chieftaincies to the south-west, he was able to achieve this between April 12 to 19. Eventually forts by the name of Luck, Marquand, Molyneaux, Khami, Dawson and Halstead were built along this road, serving as both refuges and outposts. Garlake (1965) and Cross (1972) have the most information on these forts (see also Selous 1896: 139-143) but some points are worth noting. The vast majority of forts constructed in Rhodesia in 1896-97 were of a standardized rectangular design, adapted to local terrain and the whims of the commanding officer. Those constructed between Bulawayo and Mangwe were minor forts, often nothing more than sandbagged enclosures at the summit of a kopje. Baden-Powell (1897) wrote that "They would make a sapper snort, but none the less effective for all that. They are first, the natural kopje or pile of rocks aided by art in the way of sandbag parapets and thornbush abbattis fences - easily prepared and easily held". BP himself would have a great deal of experience with such structures during the Matobo campaign.

Right, so what happened?

"The rebels based on the Umguza River and its upper tributaries represented by far the gravest threat to Bulawayo: either they had to be driven off or the town would fall" (Ransford 1968: 96). Starting on April 16, the whites began to lead several probing patrols, hoping to find and exploit weaknesses in the Matabele lines with follow ups on April 19, 20 and 22; each time the whites withdrew and "left the field… in possession of the Matabele" (Selous 1896: 145). “Singinyamatshe's [an ally of Mkwati] horn sounded throughout these early engagements” and he ably led his troops against the whites, and as Ranger (1967: 177) has argued, his presence there reveals the close cooperation between the shrines and the Matabele leaders. Matabele tactics in this area were to lure the whites across the river and cut them off and kill them. In the BSACo apologia, Grey reports a common belief held by the whites at the time about why the Matabele favored this strategy along the Umgusa. Mlimo, the whites argued, had assured his followers that if the whites were to cross the river, they would all be stuck blind, their bullets would turn to water and thus become easy prey; it has been put forth that this belief explains why the Matabele fled the field on April 25 (BSACo 1898: 10-11). It was during the battle of April 22 that a trooper won the Victoria Cross for the rescue of a comrade and another was almost qualified for, during a daring rescue of Selous (see box). Having withdrawn once again, morale of the whites in the town was probably at its lowest. Tempers flared, discipline slackened - one soldier was court-martialed for "insolence" and spirits were low. Thus it was with a great sense of relief that the townspeople watched Macfarlane lead 116 white soldiers and over 200 black levies along the road to Salisbury to one of the most decisive encounters of the whole war.

Who won?

Charge of the Afrikaners during the battle of April 25 on the Umgusa River.

The white soldiers marched out early in the morning of April 25 and unlimbered their machine guns in the area of what is the suburb of Glengarry today; it used to be a farm belonging to white hunter/trader Johan Colenbrander. The Matabele quickly engaged with them, seemingly rising from the ground in the classic "horns-and-chest" formation. The maxim gun came into action and a savage firefight lasted for an hour until Macfarlane sent in his cavalry that chased the Matabele from the field of battle. He had lost five dead and six wounded while Matabele casualties were heavy; the Chronicle reported five days later that wounded Matabele were still being seen in the area of Little Umgusa. Ranger (1967: 176) quotes Lady Grey's diary where she wrote, “All the ant-bear holes are filled with... corpses... they are only skeletons now. In several places we came across skeletons lying in the bush with the shield and assegai and sandals lying beside them”. Once again for the white perspective, we can turn to Selous (1896) for an accurate summation of events: "the whole column marched back [to Bulawayo] in good order, having had by far the most successful day since the commencement of the rebellion".

Sourced from the Zanj Financial Network 'Zfn', Harare, Zimbabwe, email briefing dated 28 March 2011

South Devon Sound Radio

South Devon Sound Radio Museum of hp Calculators

Museum of hp Calculators Apollo Flight Journal

Apollo Flight Journal Apollo Lunar Surface Journal

Apollo Lunar Surface Journal Cloudy Nights Classic Telescopes

Cloudy Nights Classic Telescopes The Savanna - Saffer Shops in London

The Savanna - Saffer Shops in London Linux Mint

Linux Mint Movement for Democratic Change

Movement for Democratic Change